Around the time I got back from my trip down South. I heard David Lipsky interviewed on NPR. It’s embarrassing how little I listen to music in favor of talk radio on NPR. I come from a very verbal family, perhaps it reminds me of being a kid and the comforting feeling I would get hearing my parents talking downstairs when I was in bed not yet asleep.

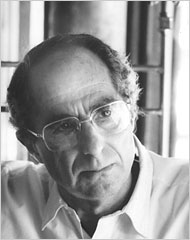

Lipsky was speaking about his book “Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself”, which is an annotated transcript of his road trip with David Foster Wallace in 1996, during the publicity tour for “Infinite Jest”. David Foster Wallace committed suicide in 2008 at age 46.

I admit to the twisted thinking pattern that committing suicide grants an artist emotional legitimacy. They are Sincere. This bona fide, and the fact that this was an account about the end of a road trip, prompted me to buy the book. Although I was grateful to be excited about reading something again, I found that the book’s insider literary focus obscured what I really wanted to know: how someone with a highly-attuned of a critical mind (David Foster Wallace) navigates his way through the meaninglessness of modern life.

David Foster Wallace himself points out, that having a writer interview another writer can make for an unrevealing article. Lipsky wants DFW to tell him how great it feels to be a famous writer. DFW doesn’t want to appear prideful so he hedges. Stalemate.

Does Wallace not want to jinx himself? Does he just want to appear more appealing? Or is he genuinely self-deprecating? That one extra question would have helped me enjoy the book more.

Lipsky otherwise is suprisingly aware and insightful. He notes that Wallace wants to impress him, but doesn’t want to be seen wanting to impress him. He notes that when Wallace’s dogs appear to like him, Wallace makes sure to comment on it – he flatters Lipsky via proxy.

I enjoyed the fact that Wallace, older than myself, considers himself a Gen-X’er, and I found it quaint that a major concern of his was T.V.-addiction. The road trip occurred in 1996, even given the times though, the idea of being concerned about watching too much t.v., watching until the 11 o’clock news comes on and then going through the Late Late Show, strikes me as kindly and nostalgic, especially compared to the massive internet addiction almost every person I come into contact now has.

After I finished “Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself”, I went out and bought “Infinite Jest” which I’ve just started. A few times in being interviewed, DFW emphasizes that he is asking the reader to do work, for which she will be rewarded later. That doing these sort of “adult” difficult things will add meaning to one’s life in oursuperficial culture.

Dave Eggers writes the glowing preface to “Infinite Jest” and although I haven’t finished the book, I’m feeling like theres a sloppiness to DFW’s writing that I also found in “A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius” Wallace at times writes dialog that sounds like it’s coming directly from his head:

( Dean of Athletics speaking about a tennis scholarship prospect)

“Just so, Chuck, and that according to Chuck here Hal has already justified his seed, he’s reached the seminfinals as of this morning’s apparently impressive win, and that he’ll be playing out at the Center again tomorrow, against the winner of the quarterfinal game tonight, and so will be playing tomorrow at I believe scheduled for 0830.” (p.2 “Infinite Jest”).

If this is page 2 I’m not sure I can make it to page 1,079. This is supposed to be one person talking to another, I’m bothered by “this morning’s apparently impressive win” and also by the whimsical “Just so”. Would you vouch for someone by saying their win was “apparently impressive”? It’s like a movie director said “give me an eccentric coach, now TURN ON THE FAUCET”.

Lipsky, when he errs, goes more for a Kerouac-style jumble:

“Wipers making weird rubbing noise because ice is caught underneath the blades; a frozen, Midwestern-style problem.” (p. 90 “Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself”).

This is not a frozen problem. It’s a real problem. And I’m sure it happens in Alaska and Siberia and the Urals. But it’s fun to decorate the narrative with that glob of paint.

I’m nitpicking here, but it’s in order to show that there is a forced “Midwestern” “average guy” sensibility being promoted that doesn’t reflect the realities of what I experienced growing up in the Midwest. And I think it does a disservice to a class of people I call “Midwestern Gothic”: guys – they are almost always men – I grew up with, now in middle-age, with an artistic sensibility, who either didn’t have the talent or the connections to become successful in the art or publishing worlds.

These are the art-school aspirants who end up staying in the Midwest and EATING IT, working low-paying jobs and making the kind of impoverished contract with modern life that strikes terror into those who have achieved greater professional success. They often are single, due to both an introspective nature and not making enough income to attract and keep a wife. They have opted-out. Society considers them to be losers. Interestingly many have cats.

Nobody cares about these guys and I wish writers like Eggars and Wallace had left some of the acrobatics aside in order to explore what it would mean to get up everyday and NOT BE SPECIAL.

In “A Heartbreaking Work…” Dave Eggars lauds brother Toph as “the greatest kid ever” at length, he describes trying to get onto MTV’s “Real World” to gain celebrity. Is the “extraordinaryism”, for lack of a better word, of his characters meant to be legitimized by the tragic circumstances they endure? That sounds like a Lifetime movie concept to me, and has little to do with a real life “loser” going to the dollar store to pick up some cat food after working his shift at the copy shop, hoping he’ll have the energy to do some digital art after dinner.

Do people just not want to read mundane stuff like this? DFW quotes Updike who says that if you write the truth and possess powers of observation, anything can become compelling. The sad fact for me here is that, once again, I am more interested in the truth of the writer’s life, than in their writing. I hope this changes as I get through the book, and I’m aware that the mundane world of an IRS office was the setting of DFW’s subsequent effort.