I haven’t written in awhile, due to a general exhaustion with popular films, the sameness of every preview I see, and the substitution of CGI for character development. Is it possible to have drama without special effects? It’s as if we are so numbed out that we forget the emotions of everyday life: the nervousness of going to a job interview, the anger felt when cut off in traffic, the happiness of seeing a loved one after a long separation. Perhaps these are not cinematic enough? I find that cartoon violence I see in so many films is largely consequence-free and thus boring. This fake violence inoculates us from fear and gives us a safe cinematic zone. One that, for some reason, seems to be needed now more than ever. Back in the first days of film, when audiences were unfamiliar with the medium, they would shy away from an onscreen speeding locomotive. Today they are only comfortable with a speeding locomotive, running over an super hero who pops up unharmed.

Another issue is the plethora of movie sequels, which I call “sequela” (“a condition that is the consequence of a previous disease or injury”). Despite this, I look forward to the upcoming Blade Runner sequel, Blade Runner 2049. It prompted me to go back and take a fresh look at the original director’s cut of Blade Runner, which is set in fast-approaching 2019.

Although it’s one of my favorite films, I find Blade Runner difficult to watch. It’s got a classic themes (the quest for immortality, what it means to be human), a love story, and is solidly in the film noir genre. Despite sweeping cinematography of futuristic night vistas and the megapolis of LA in 2019, there is also a mood of sepulchral opacity: settings are dark, rainy, crowded, smoky and harsh. Pauline Kael noted “we’re never sure exactly what part of the city we’re in, or where it is in relation to the scene before and the scene after (Scott seems to be trapped in his own alleyways, without a map.)”. The spectacular visuals don’t seem to be bound by an animating force. Completely opposite is a film like Triumph of the Will where the spectacle is in support of an idea, or in that case an ideology. And even though that ideology is odious, from a purely cinematic perspective the brightly-lit, symmetrical scenes are visually appealing and in that sense pleasurable. Whereas when immersed in Ridley Scott’s world, you end up feeling like you are on dark north wall in Game of Thrones, longing for the sunlight of the Dothraki kingdom.

What’s the idea behind this juxtaposition of beautiful structures with roiling ghettos of would-be 2019 Los Angeles? Perhaps it’s a more nuanced take on the idea of the destructive effects of technology. Technology-fueled apocalypse is well-explored territory in film: I am Legend, 28 Days Later, Brazil, Logan’s Run, Planet of the Apes, all the way back to Metropolis. Today in the news we hear Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking warning us to prepare to bow down in obeisance to our artificial intelligent overlords. In Blade Runner the apocalypse has been partial. There are gleaming palaces and flying cars, but for most it’s dirty, dark, and dusty. Humans have not been exterminated or enslaved, but live as scurrying ramen-eaters and goods-hawkers. In this sense Blade Runner is closer to Bong June-ho’s Snowpiercer than it is to most post-apocalyptic movies.

Given this grubby existence where everyone is looking out for themselves, the love story between Sean Young’s Rachael and Harrison Ford’s Deckerd should gain significance and perhaps be redemptive, but the characters are hampered by the blind loyalty to the close-mouthed film noir style. Not much is said, and not enough is felt.

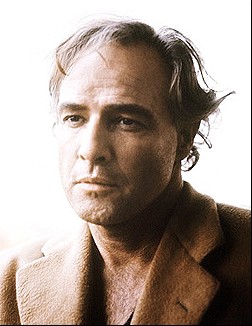

Despite these flaws, Blade Runner is an immersive, imaginative, well-acted, impeccably cast, patient film. I disagree with Kael’s assertion that Rutger Hauer stops the film every time he appears, and should win the “Klaus Kinski Scenery Chewing Award.” As the doomed prodigal son he deserves some scenery to chew and I found him energizing. Harrison Ford is at his peak but underplays the role, he always seems to have just woken up.

Blade Runner is painterly and demands a suspension of the audience’s desire to cede a portion of their critical responsibility to predictable filmic memes: buddy movie, gang of lovables, guy gets girl, righteous revenge, or what I see a lot of lately: “togetherness overcomes evil” (Guardians of the Galaxy, It). No comedy relief, no wisecracking Bruce Willis-in-Moonlighting character. It’s my favorite movie to see once every 20 years. Let’s see if the sequel leavens the bread.