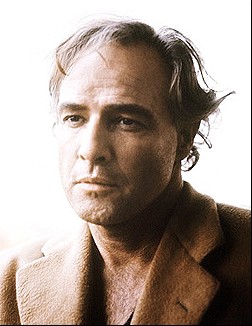

The puzzle that is Marlon Brando’s ireedemable sadness, in the face of every possible success, is only partially explained in “Listen to Me Marlon”. Stephen Riley’s recent documentary constructed from Brando’s long-running audio diary.

Richard Brody pointed out that this amazing source of material – right from the horse’s mouth – is diluted by an overbearing score and pointless audiovisual effects. I think the larger problem is what has been left out, rather than the annoying technique for what was left in.

The origin of Brando as a tragic figure, depicted so unerringly in “Last Tango in Paris,” is explored through clips of his childhood: a voiceover where he explains how his mother was “the town drunk” and his father was a cruel barroom brawler and philanderer. He describes an inability to escape the feeling that his inner nature was simply wrong.

That began to change after moving to New York, where Brando took Method acting lessons and lived with Stella Adler, who turned out to be something of a surrogate mother. This may have been the happiest time of his life.

Success and its discontents followed. On some level he did not feel he deserved the adulation. On another he overindulged in it, in order to make up for a lifetime of deprivation. It’s chilling to see interviews with the young star, awkwardly hitting on attractive female interviewers.

From this point on Brando feels increasing hounded, and disillusioned with a society he feels is obsessed with acquisition. He buys a Tahitian Island to escape and be in the company of people who don’t care that he is a movie star. Later he endures the tragedies of his daughter’s suicide, and his imprisonment (for killing his daughter’s boyfriend).

So what was left out? One subject is his relationship, possibly intimate, with early roommate Wally Cox. There was also no mention about his late-in-life friendship with talent-giant and fellow-weirdo Michael Jackson. His battles with food addiction are also barely touched upon.

But what I missed the most was Brando turning the mirror on himself. Riley focuses on the external influences that injured him: the rapacious Hollywood execs, the press, his awful early family. I keep a diary, and one of the reasons I keep it is to have a safe area where I can explore my shortcomings and any contributions I make to unhappiness in my life. The ineluctable force that was Brando as an actor – riveting despite his mush-mouthed enunciation and improbably voice – was grounded by the rare combination of knowingness combined with a deep vulnerability. In his best performances it felt like a privilege to watch him. To explore this self-awareness, it’s torments and liberations, would have made this a much better work.

Brilliant!