After seeing the Gerwig/Bambauch toy epic “Barbie” I was left with the question “Where are the girls who play with the Barbies?” The only girl character (Ariana Greenblatt) is yet another Hollywood proto-adult, who coolly condemns Barbie as “fascist”. Aside from the comic opening which pays homage to “2001” the only actual scene of a girl playing with a doll takes place in an adult’s (America Ferrara’s) gauzy flashback scenes.

Barbie is a pink fantasy version of the latest Marvel movie. Critics seem to be responding to the high concept, the tip of the hat to “camp”, without think going much deeper. I can see a Barbie franchise in the offing “Barbie XV – Skipper’s Revenge.”

This movie goes beyond action, it addresses social issues, just not in hearts and minds of girls. The movie tries to compensate by finishing with Barbie becoming more “human”, but it’s a tacked-on solution. Barbie is popular because she is not human, and although in real life Mattel offers a Barbie with a wheelchair, and a “Down’s syndrome Barbie”, those don’t sell.

The essential contradiction embodied by Barbie dolls, that they are simultaneously liberating and oppressing, must endure, because it echoes the human condition. Liberating, because Barbie shows girls that they can be anything they want to be. Oppressing because if Barbie were blown up to human-size, her waist would be so small she would not have enough intestines to digest enough food to survive. Women face the dilemma of “I want to be like that; I can’t be like that.”

Kierkegaard addressed something similar in his concept of “despair”.

“The self is a synthesis of elements which are, and will always remain in opposition. These elements are “held together” by the person and involve a tension or an anxiety which is a constant temptation to the person to “let it go”. This would be a cowardly act, destroying the self in order to escape the anxiety. The forms of “letting go” are the forms of despair.” (p. 58 Kierkegaard’s Philosophy – Self-Deception and Cowardice in the Present Age, by John Douglas Mullen).

The Barbie movie focuses on “Barbie’s” realization of this opposition. Problems start to occur when a Barbie designer attempts to avoid Kierkegaardian despair by integrating Barbie’s shadow-side via sketches and darker character ideas.

Just as Kierkegaard described those most in despair (most in normative fantasy) as seeming “in the pink of health” (pink Barbie), when Jungian undercurrents begin to flow, Barbie unpinks: she gets bad breath and flat feet.

Barbieland is veritable “Lord of the Flies” struggle for gender domination. At first the Barbie’s rule: they occupy the top echelon of society, without effort. The Kens are literally accessories. The Barbies seem to have no problem with this injustice, and a reference is made in voice-over that this is the converse of the “real world”.

After Barbie’s trip to the “real world” including visiting Mattel headquarters, populated by harmless corporate-suit dolls, Barbie returns to Barbieland only to find it now ruled by Ken dolls. The Kens have become the oppressors, forcing the Barbie’s into abject supportive roles

Two points are overlooked here. First, the comic version of hypermasculinity which the Kens embrace dilutes the parallel dilemma that boys now face. Over time boy’s “action figures” (dolls) have become more and more unrealistically muscular, to the point where they look like steroid-using bodybuilders. The dilemma of being oneself and meeting an unrealistic ideal is one shared by both genders. The male box was played for laughs.

Second, female internecine norm enforcement is ignored. The fact that it’s “impossible to be a woman” is in no way tied to female aspiration to be part of the Barbie crew. If Barbie steps out of line (plays too much) the other Barbies ostracize her as “weird Barbie”, Barbie never nurtures, Barbie never IS nurtured.

I can imagine a more interesting Nietzschean take with hyper-Barbies running amok, openly oppressing any weakness, yet succumbing to the inevitable consequences of Kierkegaardian despair: loss of meaning, identity, self. Similarly the Ken/G.I. Joe identity-havoc-wreakers would create their own personal Armageddon. The only hope, in this future and perhaps our own, would be a small girl and a boy who picks up a broken doll, strokes their synthetic hair and tells them it’s going to be OK.

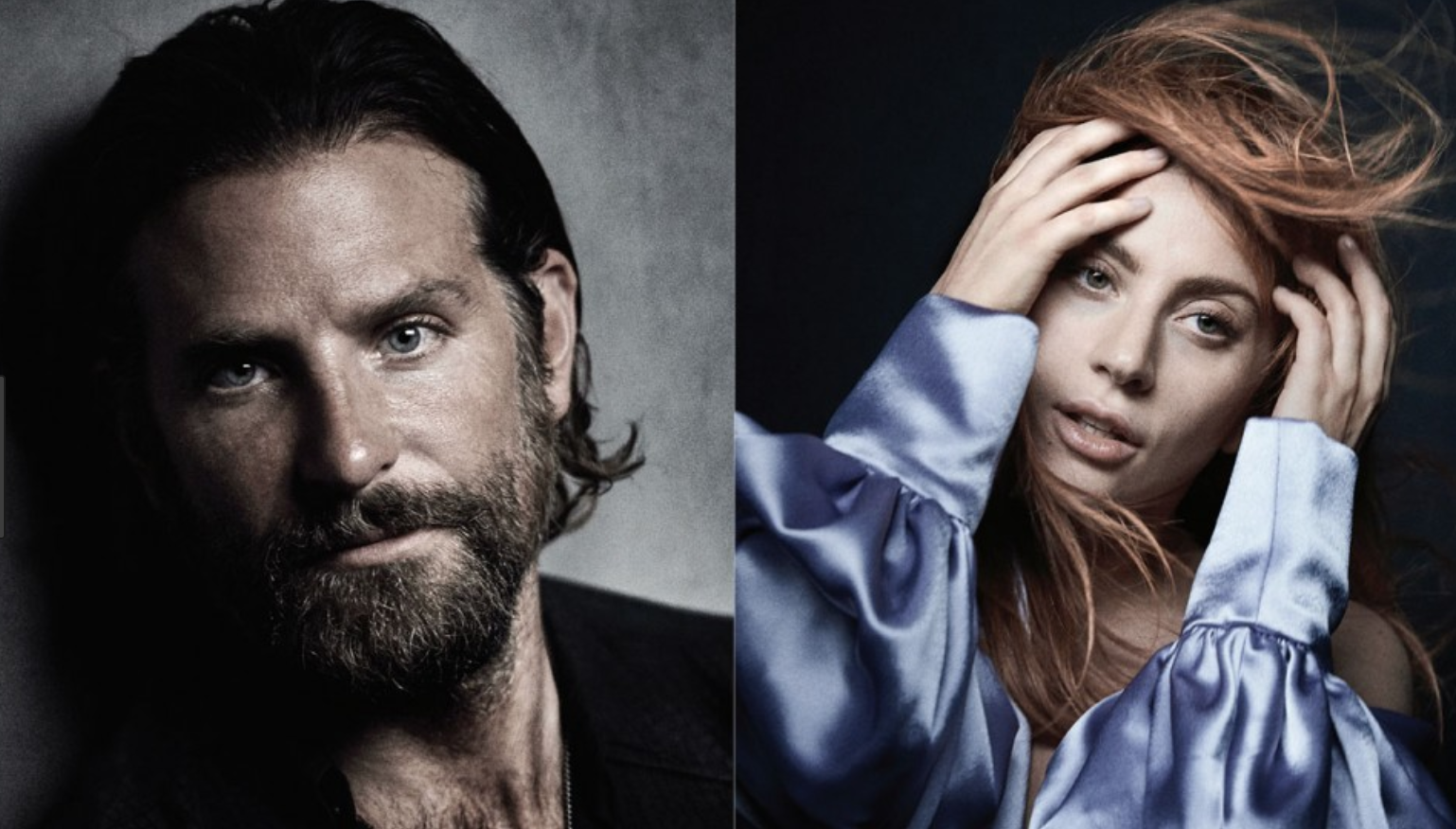

The real story of 2018’s “A Star is Born” is how its stars, who play stars, are unable to do anything but imitate how someone would behave when they achieve stardom, rather than expose their own “lived” experience.

The real story of 2018’s “A Star is Born” is how its stars, who play stars, are unable to do anything but imitate how someone would behave when they achieve stardom, rather than expose their own “lived” experience.