You would think that the decline in quality of the original 5 “Apes” movies, each one lower-budget and worse quality than the one that preceded it, would give filmmakers pause, but since 2001 we have endured 3 awful s/prequel/remakes. And yet these films do well at the box office, and are generally well-reviewed.

You would think that the decline in quality of the original 5 “Apes” movies, each one lower-budget and worse quality than the one that preceded it, would give filmmakers pause, but since 2001 we have endured 3 awful s/prequel/remakes. And yet these films do well at the box office, and are generally well-reviewed.

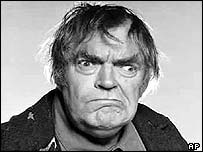

If this were the “Transformers” series I would care that much, but the original “Planet of the Apes” is indeed brilliant. Based on Rod Serling’s adaptation of Pierre Boulle’s novel La Planète des singes , it was released in 1968, and features zero CGI. Instead it featured real actors doing “acting” while wearing make-up and simian-looking prosthetics. These devices were considered advanced at the time, but now appear rather primitive:  Still how scary-looking is that? Roddy McDowell, Kim Hunter, and Maurice Evans used their costumes to enhance their performances, to give them an “otherness” that they employed, but also had to overcome in order to create full characters. This is the opposite of what Jack Nicholson said about his role as The Joker in 1989’s “Batman”, essentially to “let the costume do the work”.

Still how scary-looking is that? Roddy McDowell, Kim Hunter, and Maurice Evans used their costumes to enhance their performances, to give them an “otherness” that they employed, but also had to overcome in order to create full characters. This is the opposite of what Jack Nicholson said about his role as The Joker in 1989’s “Batman”, essentially to “let the costume do the work”.

The tension between artifice and reality is something CGI erases. While this makes for more realism, it also seems to infect movies with a slackness when it comes to developing stories and characters. Critics praise CGI and forget that a realistic wink or tear does not a character make. This was the case for the second remake of King Kong, of which A.O. Scott said:

The sheer audacious novelty of the first “King Kong” is not something that can be replicated, but in throwing every available imaginative and technological resource into the effort, Mr. Jackson comes pretty close.

Novelty and technology can’t sustain a movie for 3 hours, characters and narrative can. Inexplicably Roger Ebert called Kong II “A stupendous cliffhanger, a glorious adventure, a shameless celebration of every single resource of the blockbuster, told in a film of visual beauty and surprising emotional impact.” Roger Ebert is a wonderful human being, but I find his writing unmemorable. A.O. Scott seems to specialize in plot summaries. Plot summary + apologia that this is a “spirited” movie that isn’t perfect = A.O. Scott review.

Despite my griping, I too wanted to see chimpanzees on horseback firing machine guns (I’m only human). I found that it was just not as thrilling as what the original “Apes” movie did for me: imagine a world where humans are no longer the pre-eminent species, where it’s payback time for the creatures we have abused for millenia. Jerry Goldsmith’s eerie modernist score helped create this sense of unease – so different from the crash, boom, bang of near-constant violence in “Dawn”, which has a strange calming effect on me because it seems to be in almost every movie now, and signifies that the good guy is going to win. The other parts of the score could have been used in a life insurance commercial.

Speaking of good guys, did Director Matt Reeves have to make ape-leader Caesar into an absolute saint? Consider the strategy in the original “Apes” franchise. Caesar is a killer, but you understand his rage as he sees his enslaved ape-brothers stun-gunned, and watches his kindly guardian, played by Ricardo Montalban, die in order to protect him. I go to movies to see people who are worse than me, not better.

The final visual in “Dawn” is another capitulation to feel-good non-reality:

Recall the harrowing last scene in “Planet of the Apes” with Taylor and Nova about to enter into the Forbidden Zone after seeing the ruined Statue of Liberty:  Final verdict on “The Dawn of the Planet of the Apes”:

Final verdict on “The Dawn of the Planet of the Apes”:

“You Maniacs! You blew it up! Ah, damn you! God damn you all to hell!”

Postscript: “Planet of the Apes” features one of my favorite opening scenes in movies, Charlton Heston, the spaceship captain is smoking a cigar on the bridge, recording into his log before he goes into suspended animation:

“Tell me, though, does man, that marvel of the universe, that glorious paradox who sent me to the stars, still make war against his brother…keep his neighbor’s children starving?”

Post-postscript: Really getting tired of seeing Gary Oldman, one of my favorite actors, trotting out his American accent in these trumped-up, square-spectacled Commissioner-Gordon-type roles.

Post-postscript: Really getting tired of seeing Gary Oldman, one of my favorite actors, trotting out his American accent in these trumped-up, square-spectacled Commissioner-Gordon-type roles.