I thought “The Boys in the Band” would be a campy ridiculous movie, redeemed only by its groundbreaking status as one of the first mainstream films that dealt with homosexuality. Instead I found it to be thoughtful, serious, well-written, and brilliantly-acted. Its dubious reputation is the result of homophobic film reviewers (the dark side of Pauline Kael) and the fact that, as gay liberation blossomed, the gay community felt a need to distance itself from the subject of self-loathing.

In terms of camp, many primetime t.v. shows now feature outre gay characters for comic effect. Every “Will & Grace” and “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy” owes an immense debt to Mart Crowley (writer, producer) and William Friedkin (director). The point to this campiness in 1970 was to establish that this was not going to be a film about assimilation, about how gay people are just like anyone else except maybe more sad. Instead this film would show a (literal) walled garden where gay men acted as they would were nobody watching.

The result was pathos, similar in tone to “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1966). in which the reigning heterosexual king and queen of the movies, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, exposed a self-loathing just as deep.

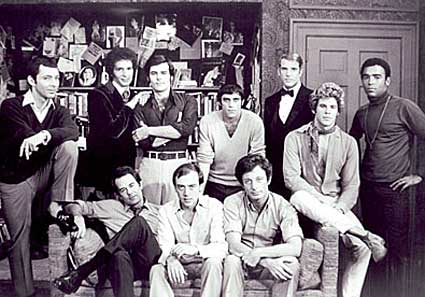

The plot is strikingly similar, an outsider arrives and witnesses the reality that lies beneath surface appearances. In “The Boys in the Band” Peter White, as straight college chum Alan, plays the naif role that belonged to George Segal and Sandy Dennis in “Woolf”. Both movies started as stage plays and feature strong acting ensembles.

Leonard Frey, as Harold, the “thirty-two year-old, ugly, pockmarked Jew fairy” is particularly compelling. And I just don’t see performances like Kenneth Nelson’ as Michael – breaking down at the end of the movie when the reality of his situation hits him – in movies today. Maybe I am watching the wrong movies. The movie ends with a note of hope: after Harold verbally demolishes hypocritical, abusive Michael, he leaves and as he is going says “Call you tomorrow…” underscoring that their friendship will survive even this . I have to admit to envying the depth of their connection, most friendships between heterosexual men, mine included, seem mannered and fearful in comparison.

“The Boys in the Band” highlights for me the terrible treatment gays have received up until a short time ago. As I’ve mentioned before, the good old days weren’t so good for gays, blacks or anyone different. Which causes me to think about which groups are marginalized today in a way that we won’t acknowledge as a society until decades hence. I think certainly animals: Jonathan Safer Foer’s “Eating Animals” seemed to me to be a necessary call-out to Michal Pollan’s evasive “Omnivore’s Dilemma”. I struggle with this issue practically daily and haven’t been able to convert to vegetarianism. Other groups might include the physically ugly – the greatest most-unspoken discrimination ever I think, the aged, and, in terms of sexuality, BDSM practitioners, acceptance of whom is slowly becoming more mainstream, at least if you go by porn as a leading indicator.

Most of the actor’s in “The Boys in the Band” died in the first part of the AIDS epidemic. To me they were brave, and their work showed us a glimpse into “real” life, often I think art, movies, films, culture are the only true public glimpse into what’s actually going on people’s heads. To dismiss “The Boys in the Band” as campy self-loathing says more about the reviewer than the film.