From the movie “Barfly”:

Jim: “You worked last year?”

Chinaski: “Six months in a toy factory. You don’t know how men suffer for children.”

Recent movies return the favor, according to Luke Epplin in his excellent Atlantic article You Can Do Anything: Must Every Kids’ Movie Reinforce the Cult of Self-Esteem?. Children’s movies now rely on “magic feather syndrome”: the plotline where a misfit child/toy/anthropomorphized animal ends up triumphing in the end by merely believing in themselves, often utilizing the very “defect” that caused them to be an outcast.

A prime example of this (which he doesn’t mention) is when Rudolph is welcomed back into two-faced Santa’s fold after successfully saving Christmas by guiding the sleigh with his formerly-hideous nose. Epplin cites many other examples: Dumbo and his ears, a garden snail winning a race in “Turbo”, a rat cooking in “Ratatouille”, a crop-dusting plane in “Planes”. It goes on an on.

He contrasts these with the 1969 animated film “A Boy Named Charlie Brown”, where Charlie LOSES the big spelling bee on the word “beagle” no less. Charlie returns home and takes to his bed for days. Linus consoles him by saying that despite losing, the world didn’t come to an end. Charlie slowly returns to daily life, nobody pays much attention to his failure, and in the final scene he takes a kick at the football Lucy is holding. In any animated kids movie today he’d kick the ball a mile. Instead Lucy pulls the ball away, as always, and he ends up flat on his back. The redemption is in not needing redemption, for this is how LIFE REALLY WORKS, and kids are actually smart enough to appreciate this.

As sleazy as Charlez Schulz has been made out to be in his personal life, “Peanuts” was a gift: a very sophisticated, humane comic. I’m reminded also of the”The Muppets”, who also weren’t afraid to make a difficult emotional point (“It’s not easy being green”) but who now have been sold to Disney in order to sell SUV’s and fast food (“It’s not easy being a delicious Subway sandwich in less than 5 minutes!!!!!!!!!”)

Pauline Kael in her review of “The Little Mermaid” makes the point that children don’t need to be spoon-fed, they thrill to darker elements:

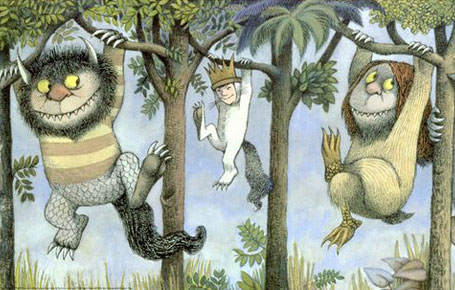

“Are we trying to put kids into some sort of moral-aesthetic safe house? Parents seem desperate for harmless family entertainment. Probably they don’t mind this movie’s being vapid, because the whole family can share it, and no one is offended. We’re caught in a culture warp. Our children are flushed with pleasure when we read them ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ or Roald Dahl’s sinister stories. Kids are ecstatic watching videos of ‘The Secret of NIMH’ and ‘The Dark Crystal.’

The question I’m left with is why are “magic feather” movies so ubiquitous today? Disney fare from the 30’s and 40’s was significantly more nuanced. One commentator to the Atlantic article suggests that it’s the stress of a post 9-11 downwardly-mobile world which encourages escapism. For all who feel uniquely stressed, remember that back in the 1960’s the Cold War was going full force and the threat of nuclear war was real. It almost happened with the Cuban Missile Crisis, 7 years before Charlie Brown was shown in theaters.

My guess is that it’s more related to the always-on-yet-emotionally-disconnected nature of e-connected life today. When you have to be able to respond at any time, you seek refuge, and the only refuge in a competitive world is being the winner. There is no Charlie Brown in his bed anymore, quietly getting up and putting his clothes on.